Contents

Hawala Banking

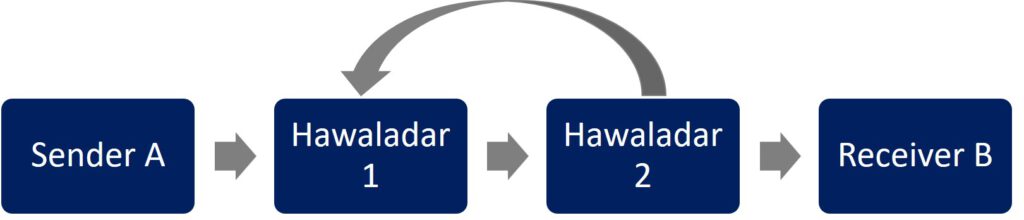

Hawala Banking is an informal method of transferring money without any physical movement of cash. It operates on a system of trust and relies on a network of money brokers, known as „Hawaladars.“

How does Hawala Banking work in real life?

Here’s a step-by-step explanation of how Hawala banking works in real life:

- Initiation of Transfer:

- A person (Sender A) who wants to send money to someone in another location (Receiver B) approaches a Hawaladar in their locality.

- Sender A gives the Hawaladar the amount of money they wish to send, along with a small commission fee for the transaction.

- Transaction Codes:

- The Hawaladar provides Sender A with a unique code or password. This code will be used to authenticate the transaction on the receiver’s end.

- Communication:

- The Hawaladar in the sender’s location contacts another Hawaladar in the receiver’s location, often through a phone call, text message, or email, informing them of the amount to be transferred and the unique code.

- Payment to the Receiver:

- Receiver B approaches the Hawaladar in their location, presents the unique code, and, upon verification, receives the transferred amount, minus a small commission fee for the transaction.

- Settling the Balance:

- The two Hawaladars will later settle the balance between them, which can be done through various means such as future transactions, bank transfers, or through a mutual settlement of debts and credits in the Hawala network.

- Trust and Reputation:

- The entire system relies heavily on trust, reputation, and long-standing relationships between Hawaladars. There are no promissory notes exchanged, and the transactions are not recorded in the formal financial system.

Hawala banking is popular for its speed, cost-effectiveness, and minimal paperwork. It’s particularly used in regions with limited access to formal banking or where the formal banking processes are slow and cumbersome. However, due to its informal nature and lack of a paper trail, it is often scrutinized for potential misuse in money laundering and financing illegal activities.

How do the two Hawaladars know each other?

The two Hawaladars typically know each other through a combination of professional networks, personal connections, community ties, or through the broader informal banking community.

- Community and Family Ties:

- Many Hawaladars belong to close-knit communities or extended family networks where connections are established over generations. These long-standing relationships build a foundation of trust that is crucial for the Hawala system.

- Business Networks:

- Hawaladars often operate within specific diaspora or trade communities where they come into contact with each other through business dealings. Networking within these communities can introduce Hawaladars to each other.

- Referrals:

- Existing Hawaladars might refer new members to the network. These referrals come with a degree of vetting and endorsement, which helps to maintain the trust and integrity of the Hawala system.

- Professional Associations:

- In some regions, Hawaladars might belong to informal or semi-formal associations that provide a platform for interaction, dispute resolution, and mutual support.

- Shared Interests or Causes:

- Hawaladars might come to know each other through involvement in shared charitable, religious, or community activities. Shared goals and interests can foster connections that later translate into professional relationships.

- Marketplaces and Social Gatherings:

- Traditional marketplaces, mosques, and social gatherings are common places where Hawaladars might meet and establish connections. These venues offer opportunities for informal discussions and networking.

- Online Platforms and Forums:

- With the advent of digital communication, some Hawaladars might connect through online platforms and forums dedicated to diaspora communities, trade, or specific interests.

The relationship between Hawaladars is built on mutual trust and respect, which is essential for the operation of the Hawala system. The trust is often underpinned by the understanding that failure to honor commitments can lead to a loss of reputation and exclusion from the community, which would be detrimental to their business.

How do the two Hawaladars settle their balance?

The two Hawaladars settle their balance through a variety of methods, often depending on the relationship between them, the amount to be settled, and the frequency of transactions they conduct.

- Offsetting Transactions:

- Future transactions can be offset against the current balance. For example, if Hawaladar 1 has sent more money on behalf of Hawaladar 2, the next transaction that needs to go in the opposite direction can be adjusted accordingly.

- Physical Cash Exchange:

- In some cases, Hawaladars might physically exchange cash to settle the balance. This could involve meeting in person or using a trusted courier to transport the cash.

- Bank Transfers:

- Though Hawala is an informal system, some Hawaladars might use formal banking channels to settle large balances, especially if they operate in regions where Hawala is semi-regulated or tolerated.

- Goods or Commodities Exchange:

- The balance can also be settled through the exchange of goods or commodities equivalent to the value of the balance. This might include precious metals like gold, electronic goods, or other valuable items.

- Services:

- In lieu of cash or goods, services might be exchanged as a form of settlement. For example, one Hawaladar might provide logistical support, real estate space, or other services to the other.

- Mutual Settlement with Other Hawaladars:

- Hawaladars often operate within a network. If multiple parties are involved, balances might be settled through a mutual agreement involving several parties within the network, effectively ‚clearing‘ the debts in a circular manner.

- Third-party Settlements:

- Sometimes, a third party who owes money to one Hawaladar and needs to receive money from the other can be involved in the settlement process, thus resolving the balance between the two original parties.

The method chosen often depends on the practicality, ease, and cost-effectiveness of the settlement, as well as the need to maintain discretion and trust within the network.

Which role do obliged entities play in Hawala Banking?

Obliged entities such as credit institutions, financial services institutions, payment institutions, electronic money institutions, and their respective agents play an unwitting role in the facilitation of Hawala banking. This role is primarily as conduits through which Hawaladars can disguise and conduct their financial transactions as part of their legitimate business activities, particularly in the trade of goods like vegetables, fruits, spices, and other commodities.

- Conduits for Disguised Transactions:

- Obliged entities become unintentional conduits for Hawala transactions when Hawaladars, under the guise of legitimate businesses, use these institutions to transfer funds. These funds, ostensibly for the payment of goods, may actually represent Hawala transfers.

- Integration into Legitimate Business Operations:

- Hawaladars who own legitimate businesses may use their commercial transactions, which involve import and export activities, to mask the movement of funds related to Hawala banking. The transactions processed by obliged entities, therefore, become intertwined with the Hawala system without the institutions‘ knowledge.

- Unwitting Participants in Regulatory Evasion:

- By processing these disguised transactions, obliged entities unwittingly help Hawaladars evade the regulatory framework designed to combat money laundering and terrorism financing. This evasion occurs because the transactions are camouflaged as routine business payments.

- Risk Exposure:

- Obliged entities are exposed to risks of being implicated in illegal activities, including money laundering, due to their involvement in processing transactions for Hawaladars. These risks arise from the difficulty in distinguishing between legitimate business transactions and those intended for Hawala banking.

- Compliance and Due Diligence Challenges:

- The sophisticated use of legitimate trade to disguise Hawala transactions presents significant challenges for these institutions in fulfilling their compliance and due diligence obligations. Detecting irregularities within seemingly routine trade transactions requires advanced monitoring and analysis techniques.

- Potential for Enhanced Scrutiny:

- In response to the misuse of their services by Hawaladars, obliged entities may need to enhance their scrutiny and due diligence processes, especially for businesses engaged in high-volume trade activities. This could involve more rigorous examination of transaction patterns and the business rationale behind large or irregular payments.

In summary, obliged entities play an unintended and indirect role in the operation of Hawala banking by processing financial transactions that are cleverly integrated into legitimate trade activities by Hawaladars. This role underscores the challenges that these institutions face in detecting and preventing the misuse of their services for purposes like Hawala banking, which seeks to operate outside the formal financial system’s regulatory purview.

What role do Hawaladars play in Money Laundering and Terrorist Financing?

The role of Hawalas and other similar service providers (HOSSPs) in Money Laundering and Terrorist Financing is a significant concern due to their unique operating mechanisms, which differ markedly from conventional financial systems. These systems, deeply rooted in trust and extensive use of non-bank settlement methods, allow for the transfer and receipt of funds across borders without the same level of regulatory oversight found in traditional banking. This typology, by categorizing HOSSPs into pure traditional, hybrid traditional, and criminal, highlights the varying degrees of risks associated with each type.

- Pure Traditional HOSSPs: These are legitimate businesses that adhere to the traditional principles of the Hawala system, providing a valuable service, especially in regions with limited access to formal banking. While they serve a legitimate need, their informal nature and lack of transparent record-keeping make them susceptible to being exploited for money laundering, often without the knowledge of the operators.

- Hybrid Traditional HOSSPs: This category includes operators who might start with legitimate intentions but become unwittingly involved in illicit activities due to the lack of stringent regulatory frameworks and oversight. Their operations may be partially integrated with the formal financial system, but the lack of comprehensive monitoring and the blend of licit and illicit funds heighten the risks of money laundering and terrorist financing.

- Criminal HOSSPs: These are complicit entities fully aware of their involvement in laundering money or financing terrorism. They exploit the Hawala system’s inherent features, such as anonymity and minimal record-keeping, to move illicit funds across borders seamlessly.

Several factors contribute to the vulnerability of HOSSPs to being exploited for illicit purposes:

- Lack of Supervisory Will or Resources: In many jurisdictions, regulatory bodies may not have the necessary resources, expertise, or inclination to effectively supervise and regulate HOSSPs. This lack of oversight provides a fertile ground for illicit activities to flourish under the guise of legitimate operations.

- Cross-Jurisdictional Settlements: The ability to settle transactions across multiple jurisdictions outside the formal banking system complicates the traceability of funds. This feature is particularly attractive for illicit activities, as it obscures the money trail and hinders the efforts of law enforcement agencies.

- Use of Unregulated Businesses: HOSSPs often operate through or alongside businesses that are not subject to financial regulation. This integration with non-financial businesses allows for the commingling of licit and illicit proceeds, making it difficult to distinguish between legitimate and illegitimate transactions.

- Net Settlement and Commingling of Funds: The practice of netting out transactions over time and the mixing of legal and illegal funds within the system make it challenging to identify suspicious transactions. The lack of individual transaction records further complicates the detection of irregularities.

The most significant concern, however, is the overarching issue of insufficient regulatory attention and resources dedicated to effectively monitoring and regulating these entities. Without a committed and resourceful supervisory framework, the inherent vulnerabilities of HOSSPs to money laundering and terrorist financing cannot be adequately addressed, posing a continuous threat to the integrity of the global financial system.

Sources:

- FATF-Report „The role of Hawala and other similar service providers in money laundering and terrorist financing“ https://www.fatf-gafi.org/en/publications/Methodsandtrends/Role-hawalas-in-ml-tf.html

- BaFin-Presentation „Hawala-Banking“ https://www.bafin.de/SharedDocs/Downloads/DE/Veranstaltung/dl_221208_GW_Vortrag_Lendermann.pdf